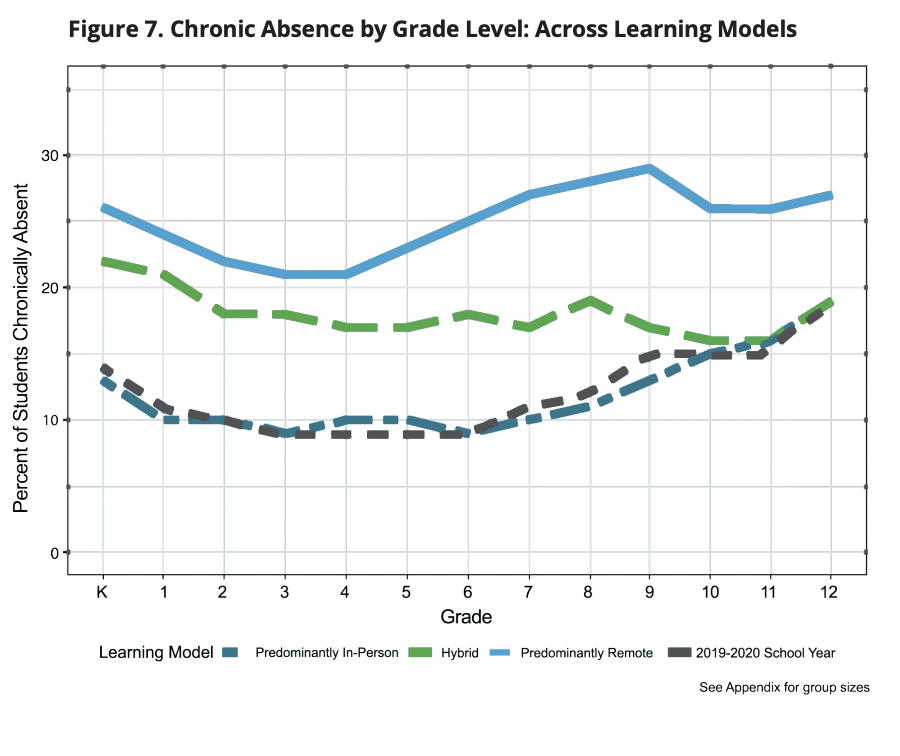

Attendance data collected throughout the past school year in Connecticut shows a disturbing finding: Chronic absence started off extremely high for all students learning remotely, affecting more than one out of four kindergartners. It remained elevated throughout the early grades, and then jumped to nearly 30% of ninth graders.

These numbers are especially alarming. Research shows that without intervention, poor attendance in the early grades can cause students to fall behind in reading. Chronic absence in ninth grade indicates students are at high risk of dropping-out of school.

Unlike most states, the Connecticut State Department (CSDE) invested in the collection of consistent, quality attendance data and public and timely release of monthly reports throughout the 2020-21 school year. As a result, the state can examine how patterns of chronic absence differed across learning modes, grades and student groups, and can use the results to inform Covid-19 educational recovery efforts and attendance initiatives. Learn more in our report, Chronic Absence Patterns and Prediction During Covid-19: Insights from Connecticut.

The insights gained from CSDE’s data collection provide useful information for everyone working to reduce the adverse impact of Covid-19 on educational inequity. For example, the data reveals:

- Chronic absence was nearly twice as high among the students participating in remote learning rather than in-person learning.

- Among hybrid learners, chronic absence was high in the elementary and middle grades but similar to in-person learning in high school.

- Among remote learners, chronic absence started off extremely high, affecting more than one out of four kindergartners, was elevated throughout the early grades and rose to nearly 30% of ninth graders. (See Figure 7).

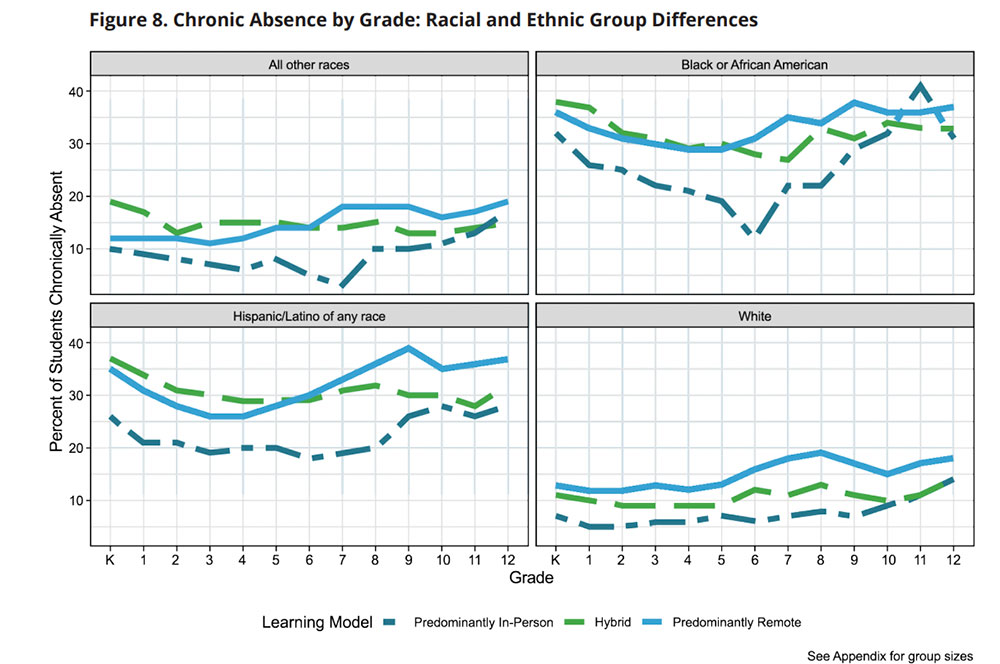

- Data broken down by ethnic background show that Black and Latino/Hispanic students are significantly more affected than white students, especially during these transition grades. (See Figure 8).

These troubling trends found in Connecticut are likely occurring in states and districts throughout the country. The metrics also highlight the crucial importance of taking action now to put in place data systems that allow for a comparison of attendance and chronic absence by learning mode.

Even if most students are expected to show up to school in-person this fall, districts still should plan for the possibility that some remote learning is needed. Some families, especially those most adversely affected by the pandemic, may be hesitant to return to in-person school. And the lack of vaccines for young children, combined with the emergence of a new highly contagious variant, means schools may still need to keep children and youth home if Covid is detected among students or staff.

What Can Districts Do?

Summer is the time when districts can and should upgrade their data systems, ensure consistent definitions of attendance in distance learning and improve their attendance taking procedures. Such investments are a strategic and smart use of Covid-19 relief funds. See the U.S. Department of Education’s guidance on using Covid-19 relief funds for implementing data-driven strategies that address chronic absence, and for developing new data quality systems.

It’s also the right time for states and districts to analyze their own data. These metrics can be used to identify which student groups have lost out most during the pandemic and ensure they are prioritized in recovery planning. Even if data is not available at the state level, districts should be able to calculate chronic absence for the past school year and disaggregate the data by grade, school and student population. Some districts may be able to examine data by learning mode.

Districts can also examine how attendance was taken and defined in distance learning. If it was much easier for a student to be counted present in distance learning, the results could be an underestimate of chronic absence levels. Connecticut, for example, required students to be present for half a day of instruction in order to be considered present. Learn more about attendance policy during the pandemic on our 50 state scan.

If attendance gaps are detected, a key next step is reaching out to students and their families. Connecticut Governor Lamont has established the Learning Engagement and Attendance Program (LEAP) to enlist the support of community partners to conduct home visits to chronically absent students and families during the summer. The purpose is to build relationships, find out what happened during the school year, connect them to resource and summer learning opportunities, and gain their perspectives on solutions to attendance barriers in the coming school year.

Student and family engagement is essential to uncovering why certain groups of students are missing school. For example, the high chronic absence among high schoolers learning with a hybrid model discovered by CSDE might reflect growing pressures for youth to work, help out with siblings, or care for sick family members while they are still in school, especially in communities hard hit by Covid. If this is the reality, schools and districts could offer students flexibility for meeting work and family responsibilities while still sustaining meaningful relationships with other students and school staff.

Taking steps now to improve attendance data systems, definitions and collection procedures offers schools early feedback about whether programs and interventions are working. And it can equip educators with insights about how to organize school in the coming year in ways that provide extra support where it’s most needed.