We had a great conversation recently with the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute. The center focuses on getting children the health care they need to show up to school ready to learn. This Q&A, which initially ran on their Say Ahhh! blog, highlights the “showing up” part of the equation.

Q: Attendance Works and Healthy Schools Campaign just released an eye-opening report that focused national attention on the importance of school attendance. Can you share some of your findings and explain why we should all worry about school absenteeism?

A: We set out to diagnose the absenteeism problem in our nation’s school, what we call “mapping the early attendance gap.”We wanted to know the who, what, when, where and why of absenteeism.

We found some things that might surprise you, like the fact that kindergartners miss nearly as much school as teenagers. Other findings were more predictable, like the fact children from low-income families are more likely to be chronically absent, meaning they miss 10 percent or more of the school year. We also found, again and again, that health challenges are part of the problem and health providers are part of the solution.

Q: Your research suggests three chief causes for chronic absenteeism: misconceptions about the importance of regular attendance, aversion to showing up for class, and barriers to reaching school every day. What role does health play in these?

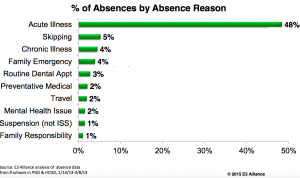

A: Health care challenges — whether physical or mental — play a part in all three. When we talk about absenteeism in this country, we tend to think about skipping school and truancy. But the reality is that illness and the lack of access to health care contribute to a whole lot of missed days. Many of these absences are excused, but the kids are still missing school and missing out on instruction.

In some cases, the illness is the barrier to attendance. Students with asthma, for instance, miss 14 million days of school a year. This is especially true for low-income children without access to a doctor who can help them manage the condition. A parent’s illness, whether related to physical or mental health, can also make it hard to get to school every day.

In some cases, aversion is connected to illness. The kindergartner who complains of a stomachache may actually be anxious about going to school. The high school student who skips school may actually be depressed.

In terms of misconceptions, these come into play in the early grades when families don’t realize how important attendance can be. They need help figuring out when they should still send their child to school because, for example, they just have a mild stomachache or if their child is truly too sick for school. Access to a doctor or a clinic can help with this.

This research summary from the Healthy Schools Campaign documents how health factors contribute to absenteeism.

Q: I was astounded to read that a full 20% of children ages 5 to 11 have at least one untreated decayed tooth and that dental problems account for nearly 2 million lost school days each year. Even if a child with a toothache is able to get to school, I can imagine that the pain would interfere with concentration and learning.

A: That’s exactly right. The pain from toothaches can cause children to miss school or lose concentration when they’re in the classroom. Other students miss school for dental appointments. Prevention is key here. The fact is many low-income students don’t have regular access to a dentist. Some schools are dealing with this by bringing dental services to school campuses. A promising model in California, called tele-dentistry, involves a dental tech coming to schools for check-ups and X-rays and referring students with cavities to a dentist.

Q: Your report also mentioned the importance of mental health care. Lower income families have fewer resources available to address childhood anxiety and depression, and their children are often exposed to more stress and trauma in their lives that could trigger mental health issues. What improvements would you like to see in this area?

A: The absences that result from mental illness are harder to quantify but are just as significant as the physical problems that keep students from getting to school. You mentioned trauma. Children suffering from trauma because of violence in their communities or their lives sometimes act out in class, leading to suspensions and more missed days. As I said before, anxiety and depression keep some students home, as do their parents’ mental health challenges. And if they don’t have access to counseling services, the problems only get worse.

Schools are seeing some success when they partner with community providers to bring mental health counseling to school campuses. Mentoring by school officials, volunteers or older students can also be an effective strategy. Also there is a promising national trend toward creating more positive, supportive school environments sensitive to the needs of children suffering trauma.

Q: Can you comment on how early diagnosis and treatment for children is connected to school attendance?

A: Early diagnosis is key to getting children off to a strong start with attendance. If we can get ear infections under control early on, we can cut down on absenteeism. If we identity the children who need support for developmental delays and learning disorders, and provide treatment we can help them become stronger, more engaged students. Teachers tell us that some of the aversion-related absences come when children suffer undiagnosed learning difficulties and don’t feel like they can be successful in school. This is also true for children with vision and hearing problems.

It’s important to remember that absenteeism starts early and, if not addressed, leaves students struggling to catch up in the later grades. Our interventions need to start early, too.

Q: Many of the health barriers to attendance that your report mentions are preventable and/or treatable if the child has affordable, quality health care coverage. Can you comment on the importance of affordable, comprehensive health care coverage to supporting children so they can show up for school ready to learn?

A: Access to quality health care is absolutely essential to improving school attendance. When Santa Clara County, California, expanded health coverage to all children, parents reported that both health and school attendance improved.

Access to a good health provider not only means that children and families can manage treatable conditions, such as asthma and tooth decay, it also gives them access to a trusted provider who can help navigate when a child is too sick for school. A doctor or a nurse can deliver the message about the importance of attendance in a far different way than a truant officer or attendance clerk can.

Q: Your organization encourages people to “Think Outside the Classroom” – can you elaborate more on what you mean by that?

A: Given that so many factors outside the classroom influence absenteeism– health, housing and transportation, to name a few – we can’t expect schools to solve this problem alone. I’ve already talked about the important role that health providers can play. Public health officials can help, using the health data they collect – hospital visits, lead exposure, concentrations of asthma – to identify where students and families need more support.

Beyond health, we’re seeing housing authorities launch attendance initiatives to raise awareness among their tenants, faith leaders organizing volunteers to reach out to families, transit agencies providing free service to students headed to school and businesses contributing prizes for attendance competitions. The whole community can get involved.

Q: Many uninsured children are eligible for Medicaid and CHIP coverage but not enrolled. Do you have any thoughts on how to get more children connected to affordable health coverage?

A: California offers an especially interesting effort to address this solution. Last year, it passed legislation requiring schools to inform families about their health coverage options in the beginning of the year. This All in for Health Campaign , just launched this year, has the potential to make sure uninsured children get the health coverage they deserve. Models that use trusted advisers, such as community health workers, have been successful at enrolling eligible children in health insurance. Some of these models are school-based, others are school-linked or have a partner relationship with a school district.

Q: A report we just released on the long-term benefits of Medicaid found that children with Medicaid coverage are more likely to graduate from high school, attend college and grow up to be healthier more financially successful adults. Does that sound consistent with what your research has shown about school absenteeism?

A: We have found that students who miss too much school in the early grades are less likely to read well by the end of third grade, a key milestone for student success. By sixth grade, chronic absence becomes a leading indicator that a student will drop out. A student who is chronically absent any year from 8th through 12th grade is 7.4 times more likely to drop out. And as your report shows, high school dropouts are less likely to lead healthy, productive lives. Given the role that poor health plays in absenteeism, it’s safe to say that health is directly connected to achievement gaps and dropout rates.

Q: Have you done any research on whether the insurance status of parents impacts a child’s school attendance?

A: No. We have not conducted such research ourselves. But, it is well worth exploring since we know poor parental health can contribute to missing school especially for young children who depend upon adults to help them get to class.

Q: Your latest report made a big splash. What’s next for Attendance Works?

We’re looking forward to some events very soon that will shine a spotlight on districts and states that are doing a good job addressing chronic absenteeism. We just released a list of 200+ superintendents who are tackling this issue by analyzing data, bringing in community partners and using other strategies. We’ll be finding ways to share their stories. Next spring, the federal government will — for the first time — release data showing how many students miss too much school. We’re hoping to equip districts with the tools they need to turn around poor attendance.

Q: Thanks Hedy. We look forward to collaborating with you again soon to focus on the health and educational needs of America’s children.

A: Thank you. It would be a pleasure.